And if so, was anyone really listening?Ĭertainly if there were places in west Texas where stories might sometimes be told, those places would be the local Dairy Queens: clean, well-lighted places open commonly from 6 A.M. spot a loquacious villager who - even at that late cultural hour - might be telling a story. On that morning in 1980, Benjamin's tremendous elegy to the storyteller as a figure of critical importance in the human community prompted me to look around the room, at that hour of the morning lightly peopled with scattered groups of coffee drinkers, to see whether I could. Whether what he favored actually occurred, as opposed to remaining potential, is a question I want to consider in this essay. The Dairy Queens, by providing a comfortable setting that made possible hundreds of small, informal local forums, revived, for a time, the potential for storytelling of the sort Walter Benjamin favored. What I remember clearly is that before the Dairy Queens appeared the people of the small towns had no place to meet and talk and so they didn't meet or talk, which meant that much local lore or incident remained private and ceased to be exchanged, debated, and stored as local lore had been during the centuries that Benjamin describes. The extent to which it was moral is a question we can table for the moment.

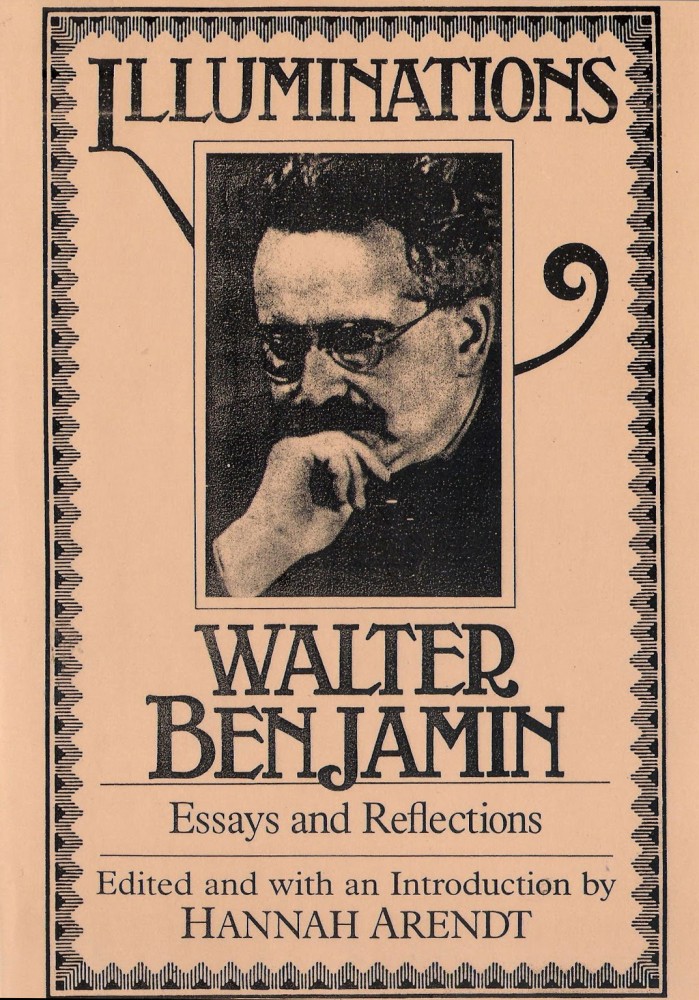

The aridity of the small west Texas towns was not all a matter of unforgiving skies, baking heat, and rainlessness, either the drought in those towns was social, as well as climatic. Dairy Queens, simple drive-up eateries, taverns without alcohol, began to appear in the arid little towns of west Texas about the same time (the late sixties) that Walter Benjamin's work began to arrive in the English language - in the case of Illuminations, beautifully introduced by Hannah Arendt. The place where I first read the essay, Archer City's Dairy Queen, was apposite in more ways than one. In the summer of 1980, in the Archer City Dairy Queen, while nursing a lime Dr Pepper (a delicacy strictly local, unheard of even in the next Dairy Queen down the road - Olney's, eighteen miles south - but easily obtainable by anyone willing to buy a lime and a Dr Pepper), I opened a book called Illuminations and read Walter Benjamin's essay "The Storyteller," nominally a study of or reflection on the stories of Nikolay Leskov, but really (I came to feel, after several rereadings) an examination, and a profound one, of the growing obsolescence of what might be called practical memory and the consequent diminution of the power of oral narrative in our twentieth-century lives. Throughout, McMurtry leaves his readers with constant reminders of his all-encompassing, boundless love of literature and books. McMurtry writes frankly and with deep feeling about his own experiences as a writer, a parent, and a heart patient, and he deftly lays bare the raw material that helped shape his life's work: the creation of a vast, ambitious, fictional panorama of Texas in the past and the present.

Pepper to the lost art of oral storytelling, and describes the brutal effect of the sheer vastness and emptiness of the Texas landscape on Texans, the decline of the cowboy, and the reality and the myth of the frontier.

He praises the virtues of everything from a lime Dr. Using an essay by the German literary critic Walter Benjamin that he first read in Archer City's Dairy Queen, McMurtry examines the small town way of life that big oil and big ranching have nearly destroyed. In a lucid, brilliant work of nonfiction, Larry McMurtry has written a family portrait that also serves as a larger portrait of Texas itself, as it was and as it has become.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)